Baum was a natural entertainer, and so his stint as a playwright and actor brought him the greatest satisfaction out of these early employments, but the work was not steady, and the lifestyle disruptive.īy 1882, Baum had reason to desire a more settled life. In his 20s, he raised chickens, wrote plays, ran a theater company, and started a business that produced oil-based lubricants. “You see, in this country there are a number of youths who do not like to work, and the college is an excellent place for them,” he said.īaum did not mind work, but he stumbled through a number of failed enterprises before finding a career that suited him. That was the end of his tenure in Peekskill, and although he attended a high school in Syracuse, he never graduated and disdained higher education. At 14, in the middle of a caning, Baum clutched his chest and collapsed, seemingly suffering a heart attack.

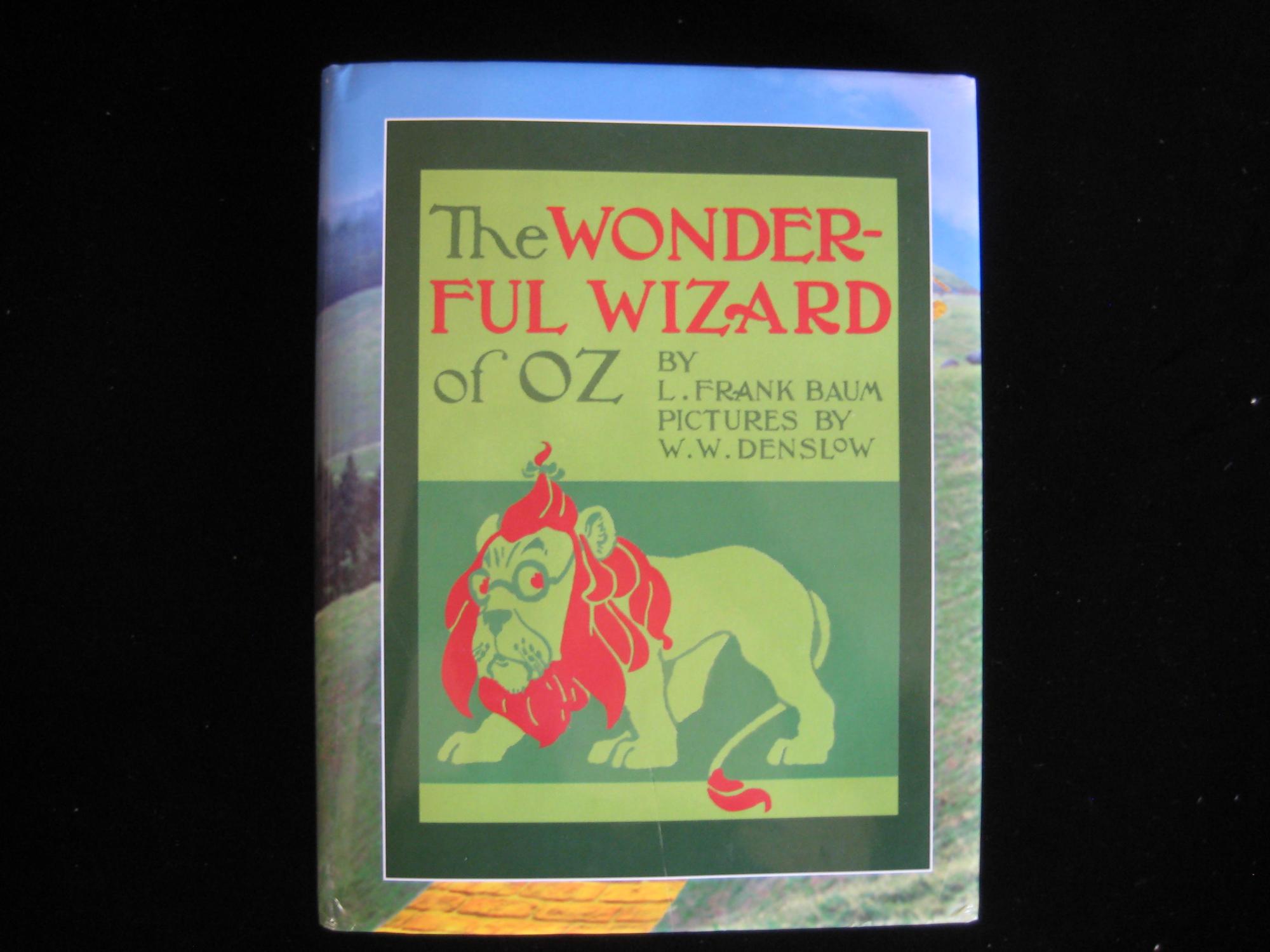

As Schwartz details in his comprehensive and entertaining book, Baum was sent to Peekskill Military Academy at age 12, where his daydreamer spirit suffered under the academy’s harsh discipline. Schwartz (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt).īorn in 1856, Frank Baum (as he was called) grew up in the "Burned-Over District" of New York state, amid the myriad spiritual movements rippling through late-19th-century society. Frank Baum Discovered the Great American Story by Evan I. Wouldn’t we all be forever lost without “there’s no place like home,” the mantra that turns everything right side up and returns life to normalcy?īut the icons and the images did originate with one man, Lyman Frank Baum, who is the subject of a new book, Finding Oz: How L. It seems incredible that one man injected all these concepts into our cultural consciousness. Reflecting on all the things that Oz introduced-the Yellow Brick Road, winged monkeys, Munchkins-can be like facing a list of words that Shakespeare invented. Today, images and phrases from The Wizard of Oz are so pervasive, so unparalleled in their ability to trigger personal memories and musings, that it’s hard to conceive of The Wizard of Oz as the product of one man’s imagination. When an alternate pair of the famous slippers went on the market in 2000, they sold for $600,000. In its attempt to draw crowds, the museum didn’t underestimate the footwear’s appeal. Posters displaying a holographic image of the sequined shoes from the 1939 MGM film The Wizard of Oz beckoned visitors into the redesigned repository. When the National Museum of American History reopened last fall after an extensive renovation, ruby slippers danced up and down the National Mall.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)